Storage, Preservation and Icehouses

In the days before

refrigeration, food was carefully stored in cellars or larders in the cool

basement. As food could not be kept for long, a lot of preserving and pickling

took place at

At rich houses

which were not so well equipped, the ice-man was called upon to bring a large

dripping block of ice before a party. The blocks were imported from

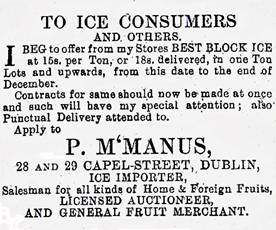

Advertisement for Ice-Importers

Instead bacon was

cured, beef and mutton were salted, and fish was smoked, salted or pickled. The

traditional way of curing bacon was to rub the pork fat with salt and water.

The shelf-life of meat could be extended by curing it dry, by smoking it in the

chimney over a wood or peat fire. Meat or fish could also be potted or baked in

a pie, which could be kept for several weeks under an airtight sealing of

clarified fat. Venison was stored in the game-house, where it might hang for

several weeks til ‘gamey’.

The Victorian

upper-class ate great quantities of meat and their dinner menus usually

included a number of different hot and cold meat courses. While mutton was the

main meat enjoyed by the poorer Irish, the rich enjoyed beef, lamb, veal and

venison along with poultry and rabbit. Beef was a preserve of the upper classes

and was consumed in great quantities. Veal was a little more expensive, but was

still a favourite on the dinner table, where the head and brains might be

served up as a delicacy. At Emo, the servant known locally as “Hannah the

Black” reportedly reared veal for the house in her retirement.

Victorian game pie

Cheap mutton and

poor veal may have served for ordinary dinners, when the family was not

entertaining. Chicken and duck were served as savoury dishes along with

pheasant, woodcock, lark and snipe. Meat was roasted on great spits in the

kitchen, above large pans which caught the dripping. It was also boiled,

broiled or made into pies. Cooked meat was served with rich gravy or sauces

such as ramonade sauce (a hot pepper sauce for cold

meat or game), sauce Robert (for pork), truffle sauce (for chicken and game)

and chestnut sauce (for turkey).

Roast pheasants with chips and brown crumbs

(Mrs Beeton)

Jugged meat was

also popular, with jugged hare or pigeon often gracing the dinner table. The

tradition of cooking and serving meat in jugs goes back to the medieval period,

when several jugs would be economically placed together in a large cauldron of

boiling water. The traditional method was to cook the meat in a tall closed pot

without gravy, the natural juices ensuring that it cooked moist and even. By the

Victorian period, wine and beef stock might also be added to the jug, with

sauce poured over it before serving.

The Victorians had

no qualms about eating parts of animals seldom eaten by the Irish today. Mrs Beeton’s book, for example, includes recipes for sheep’s

brains with matelot sauce, stuffed bullock’s heart,

ox-cheek soup, stewed calf’s ears and fricassee of calf’s feet, to name but a

few. The upper-classes were also no strangers to strong-tasting meat - venison,

for example, might be hung for several weeks til

‘gamey’ and ‘rescued’ with brine when turning rancid. Ox tongue was one of the

few offal dishes eaten by the aristocracy; tripe, for example, was more

commonly associated with the lower social classes. Cold tongue was served as a

snack or picnic food, while ‘spiced tongue’ was a Christmas favourite, spiced

with ginger, cloves, nutmeg and allspice and cooked with onions and

carrots.

Roast hare in red currant jelly

(Mrs Beeton)

Fish mentioned on

Irish country house menus include salmon, eels, oysters, lobster, cod, haddock

and trout. On aristocratic dinner menus, fish was usually a supplement to meat,

and was always greatly outnumbered by meat and poultry dishes. In the early

period, much of the fish was salted, pickled or smoked for preservation. Salted

cod and pickled salmon or oysters feature widely in early menus, along with the

ubiquitous kipper. In large houses, vast quantities of herrings were

traditionally salted for the winter and stored in barrels in between layers of

salt. Smoked eel, one of the oldest foods in

Fish-shaped fish pie

Improvements in

rail transport meant that marine fish could be delivered fresh by the Victorian

age. In 1848, for example, a ‘sumptuous repast’ served to 200 guests at

A popular brand of anchovy relish

Imported anchovies

were also very popular on the tables of the wealthy, favourite recipes being

‘anchovies and parmesan cheese’,

‘anchovy toast’ and ‘anchovy sauce’. Large quantities of kippers and oysters

would also have been bought in. At Abbeyleix, for

example, kippers and oysters were regularly bought by the 100, the former

serving for breakfast or sometimes marked as ‘for servants’. Oysters generally

appear as second courses, sometimes baked in the oven, sometimes marinated.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, oysters were very cheap

and were eaten by all social classes. They were still inexpensive by 1800,

when 100 oysters cost 2s 2d. In the mid-19th century, however,

oysters suddenly went from being a staple of the poor to a luxury of the rich,

due to overfishing and pollution.

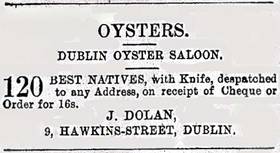

Advertisement for fresh oysters